Summarized History

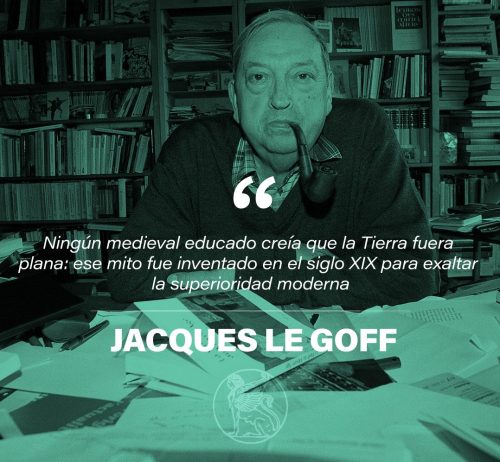

Jacques Le Goff, in his effort to dismantle the stereotypes associated with the Middle Ages, addressed the myth of the supposedly widespread belief in a flat Earth during this period. In works such as The Middle Ages Explained to the Young (2006), the French historian argued that the idea that the medieval people ignored the Earth's sphericity was a later invention, arising in the 19th century as part of a narrative that sought to exalt modern scientific progress in contrast to a past imagined as backward. This myth, according to Le Goff, was consolidated in the context of nineteenth-century positivism and European colonialism, which needed to present non-Western societies - and pre-modern European history itself - as inferior in order to justify their cultural and political dominance.

The belief in a spherical Earth, in fact, was widely accepted among medieval scholars, heirs of classical and Hellenistic traditions. Authors such as Isidore of Seville (7th century) and Bede the Venerable (8th century) described the world as a globe in their writings, while scholastic texts of the 13th century, such as those of Thomas Aquinas, reiterated this knowledge based on Aristotle and Ptolemy. Even the best-known medieval maps, such as the mappae mundi, which depicted the Earth as a disk, were not intended to be literal interpretations of its shape, but symbolic diagrams that organized sacred and profane spaces according to a religious worldview.

Le Goff points out that the misrepresentation of this knowledge began with the Enlightenment, when philosophers like Voltaire caricatured the Middle Ages as an age of ignorance to highlight the achievements of modern reason. However, it was in the 19th century when the myth was popularized by writers such as Washington Irving, who in his fictionalized biography of Columbus (1828) spread the idea that the navigator had fought against planist theologians. This narrative was taken up by nationalist historians and scientific popularizers to construct a simplistic opposition between "medieval obscurantism" and "modern rationalism", thus hiding the continuities between the two periods.

For Le Goff, this myth not only distorts history, but reveals a methodological anachronism: projecting onto the past the categories and conflicts of the present. By demonstrating that terrestrial sphericity was a consensus among medieval educated elites, the historian underlines that the Middle Ages was a period of critical dialogue with the classical legacy, not of absolute rupture. His analysis is part of a broader project to rehabilitate the Middle Ages as a dynamic era, where religious thought, scientific curiosity and technical innovation coexisted. By deconstructing the myth of the flat Earth, Le Goff not only corrects a factual error, but also questions the ideological instrumentalization of history to legitimize discourses of cultural superiority.

Other related articles: